We were delighted to partner with LSW, a long standing CaSE member, to run this event, and to have the lecture given by Professor Wendy Larner, who took up the post of President and Vice-Chancellor of Cardiff University in September 2023. Below you can find a brief summary of the event as well as a full transcript of Professor Larner’s talk.

Summary

It was fantastic to hear from newly elected LSW fellow Professor Wendy Larner about her vision for Cardiff University, how the university sits within the industrial and geographical context of Wales, and the challenges facing the university sector as a whole. We then had some excellent questions from eminent figures in the sector prompting many thought-provoking discussions. The Q&A covered topics such as how the sector can most effectively work with the government on policy developments, the important role of businesses in advocating for universities, and the learnings that can be drawn from Prof Larner’s experiences of the challenges faced by the New Zealand research system.

The day was a brilliant opportunity for CaSE to work with our membership and continue our engagement with R&D stakeholders in the devolved nations. It was also great to hear about how our public attitudes regional analysis work has been enriching policy and advocacy discussions within Wales. We are looking forward to future opportunities to work with partners across the devolved nations.

Full Transcript

What kind of university, for what kind of future? – Professor Wendy Larner

I’m a newcomer, having arrived in Wales nine months ago. I have to say that I am absolutely delighted to be here. I regularly talk about the commonalities between New Zealand and Wales; it’s what drew me to this role: the Wellbeing and Future Generations Act and the commitment to multigenerational thinking; the seriousness with which both countries take the challenge of climate change and biodiversity; the strong investment in enhancing environmental, economic and social justice, and last, but not least, the experiences of both multiculturalism and bilingualism. And I haven’t even mentioned rugby! Of course there are also important differences, but Wales is a great place from which to think about possible futures for both universities and the world.

In addition to being the new Vice-Chancellor of Cardiff University I’m a human geographer by disciplinary background. In my academic work I have long been an adherent of situated knowledges, I’ve always been interested to ask what does it mean to theorise from a time and place. These are not parochial knowledges, if they are done well they speak powerfully to global concerns. I’ve tried to do this in my academic work – using what a referee once uncharitably described as my quirky little New Zealand case studies to speak back to wider debates about globalisation and neoliberalism – and I now bring this orientation to bear in my organisational work. Context matters, place matters, specificity matters. What is right for one place might not be right for another. This is the thinking I’m bringing in to my new role.

It will come as no surprise to you that it is tough times for universities. Indeed, I think it is an existential moment. I’m not daunted by this; universities have had to reinvent themselves over and over again since they were first established in the middle ages. But I am clear that it is another of those times; the university model that I grew up with; publicly funded and nation building, and then massification and ever increasing numbers of students, is now morphing into a new model. That’s why when I arrived at Cardiff University I launched a major engagement and futures exercise in which I asked the question that gives us the title for this lecture: What kind of university, for what kind of future?

Let me begin by doing some scene-setting

In addition to meeting my new colleagues, I’ve spent much of the last nine months learning about my new country and city. Before I started my formal role I walked the Coast Path in North Wales. In addition to enjoying the beaches and exploring the castles, I learned about the long history of extractive industries in Wales; copper, slate and coal. I visited communities that had established themselves around these resources, and saw what had happened as demand changed and these industries were superseded by others (or not as the case may be). I began to understand the sustained pattern of English and Scottish ownership of key Welsh assets, and the wider links to Empire. In particular, Charlotte William’s book Sugar and Slate helped me understand that money from the slave trade had helped pay for industrial development of Wales.

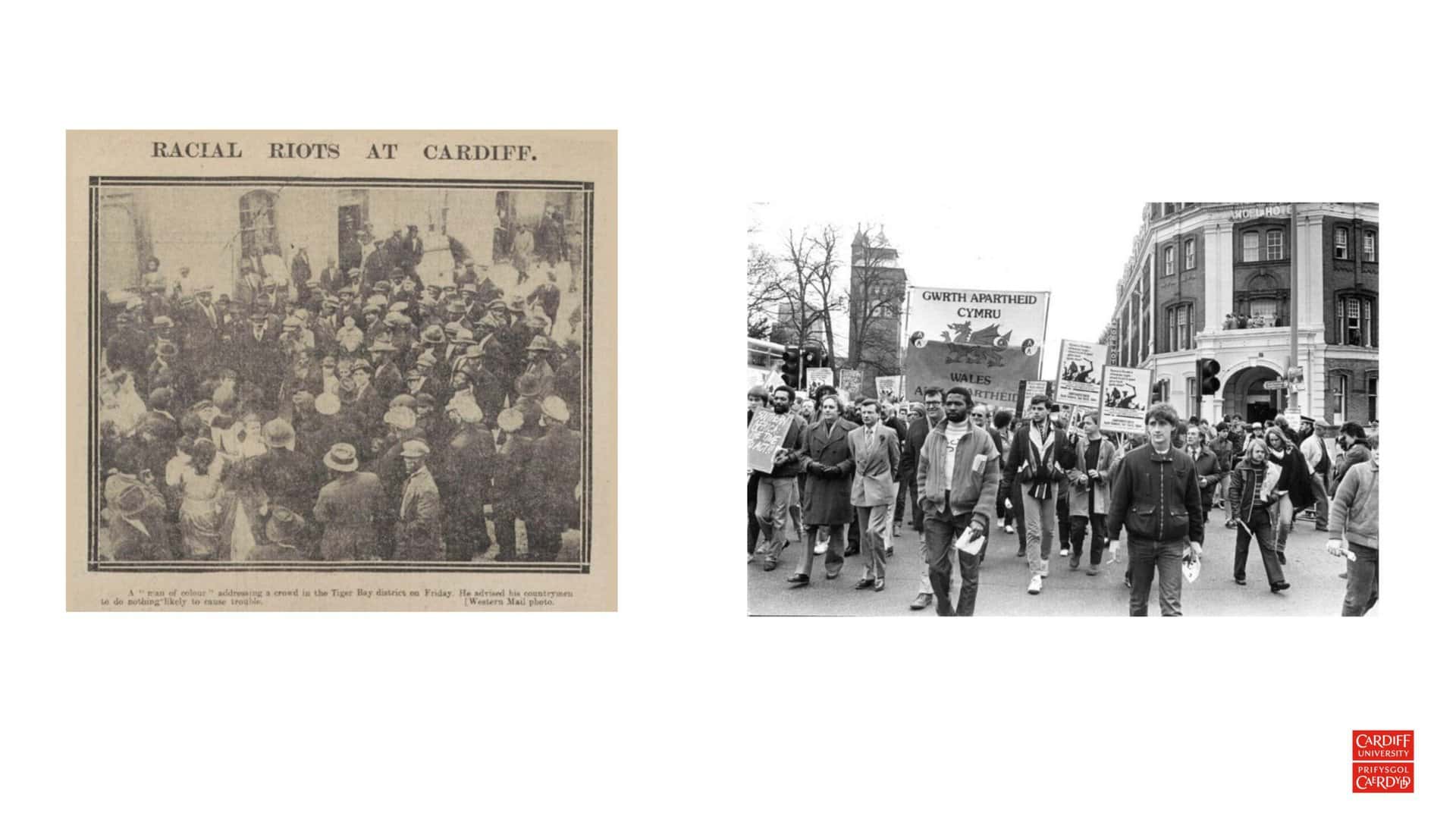

I then spent my first few months in Cardiff living in Butetown, the heart of the former Tiger Bay where the dockworkers – first from rural Wales and then from all over the world – lived as the south Wales coal industry fuelled the industrial revolution around the world. I learned Cardiff has the second oldest mosque in the UK (only after Liverpool), I was told about the Cardiff Five, and I witnessed first-hand the legacies of racism and social inclusion as I walked to the University each day. It was apparent that the city became whiter and wealthier as I went from my flat in the large gated urban regeneration project that had displaced historic Tiger Bay, north under the railway line to the Civic Quarter located on land that had formerly belonged to the Bute family. But of course, Lord Bute himself was a Scot who – despite his vast economic interests in Wales – was only an ‘occasional visitor’ to Cardiff.

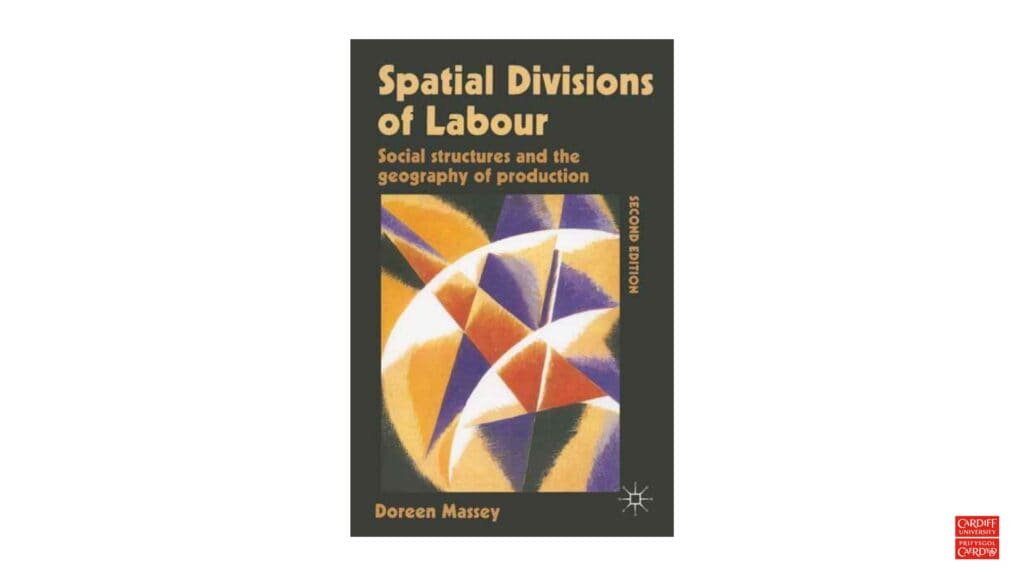

I’m a walker, so it didn’t take me long to begin exploring further afield including the Welsh Valleys. It’s really geeky, but I can’t tell you how excited I was when I found myself in the heart of the area discussed in Doreen Massey’s classic ‘Spatial Divisions of Labour’. This book explains why I became a feminist economic geographer. For those of you who don’t know it, it was published in 1984 and explores the post war economic geography of the UK, examining the decline of male dominated industries such as mining and the rise of female dominated jobs in the consumer goods industries and service sector. The South Wales valleys feature prominently in her account, and she explains how these communities have long been part of what geographers call a ‘branch plant economy’, dominated initially by English capital and then more recently by off-shore ownership of key industrial sectors.

And now of course, I’m beginning to get to know the wider Cardiff Capital Region; the clusters of economic activity consolidating around new industries such as compound semi-conductors, creative industries, medtech and fintech. I’ve met my counterparts in the NHS and local government and begun to understand something about the huge financial pressures they are under. I’ve met key Ministers in the Welsh Government, all of whom are committed to making devolution work for Wales, but find themselves grappling with ever-declining public sector budgets and tussles with Westminster. And, as I am regularly reminded by many of those I meet, the success of Cardiff University is crucial to the success of both Cardiff and Wales. No pressure!

Already I can see how important investment from elsewhere remains in Wales. Like others I was pleased to see PWC’s announcement of significant growth in their Cardiff-based activities, and the explicit identification of strong universities as part of the rationale for their decision. And, like others, I was dismayed to hear of the job losses in Tata Steel and watched the interviews with fathers and sons who had seen the steel works as their economic future and despaired for their communities. But with my economic geography hat on, I want to put these changes into the longer historical context I’ve touched on above, and explore what that might mean for the University I have the privilege to lead, and the future Cardiff and Wales our staff, students and partners might co-create.

I want to go back to Doreen Massey who – as always – has helped me think about the context I find myself within. She explains that the challenge with Wales being a branch plant economy, and the ‘semi-colonial nature of much of the early development of capitalism’ (Massey 1984:200) is that the supply of investment funds and entrepreneurial talent has always been limited. She attributes this to the lack of a local capitalist class committed to growing production within Wales. She explains that because early on private capital in the coal industry was replaced by state ownership, this saw big capital largely abdicate its relationship with Wales. Interestingly, particularly in the current era where we look enviously at initiatives like Northern Gritstone (the investment company working with universities in the north of England to create ‘the Silicon Valley of the North’) Massey says that in this regard Wales is different to other UK coal mining areas where – as we see in the north of England – big capital (and old families) remained more involved in their regions through civic institutions and their universities.

Massey also helps us understand other aspects of our present. As I noted above, she was focused on changes in the industrial geography of the UK, exploring what happens as women become economically active in low wage branch plants producing consumer goods, and jobs for men shift from coal mines to car assembly plants. Her argument was that Wales was participating in the process of ‘multi-nationalisation’ – the process we now call economic globalisation. The ownership of these new manufacturing facilities was from offshore, and she touches on the national and interregional competition that arises every time there was an announcement of the establishment of a new overseas owned facility. Sound familiar?

She notes the lack of attachment to the region in which these overseas facilities are located, explicitly observing that they didn’t need the local university because the R&D was done elsewhere. Because of the satellite and production-only status of much of the incoming industry there was a lack of senior management, and too often there was the experience of ‘negotiating with ghosts’ (pg 218). Middle and lower managers who were building their career through the company would inevitably need to move away. She also argues that the smallness of Wales matters; not only are major markets elsewhere but also inputs and components have to be brought in from outside the region, underlining the embeddedness of Welsh activities within wider divisions of labour.

Finally, Massey wrote about what these changes meant for Cardiff. She says that those ‘good jobs’ generated in this new economy – largely in middle and lower management – tended to be occupied by people based in the city where the state administration was also expanding. Presciently, she points to the growth of geographical and social polarisation and complex patterns of commuting, as the valleys increasingly were becoming dormitory towns of Cardiff. Finally, and even more presciently, she gestures towards the need for more professionals, scientists and technologists if Wales was to move away from being a branch-plant economy, and the need for these actors to be entrepreneurial. She underlines the importance of universities in this context, and identifies the emergence of the then relatively new phenomena of ‘science parks’.

What I had seen in my early explorations in north Wales, the Valleys and Cardiff, and what a return to Doreen Massey’s work underlined for me, is the ambiguity and precarity of the Welsh economy. Historically ownership and control of key economic sectors has never really been here, which means that decisions about long term investment are often made elsewhere. While Spatial Divisions of Labour may have been written forty years ago it is clear that many of Massey’s observations about Wales still hold. Her book also points to trends that are still with us; the growth in so-called ‘women’s work’ such as service industries, clerical and administrative work and the long term decline in ‘men’s work’ in labour intensive manual industries. You’ll be aware that the NHS is now the largest employer in Wales, currently employing close to 100,000 people; a very different picture to that associated with the heyday of an extractive economy centred on mining.

So what does this mean for our present?

While our political economic history remains with us – social scientists talk about path dependency – forty years on much has changed. We now understand the existential challenge of climate change and the need for a just transition. Wales has a devolved government that is increasingly charting a distinctive political course for this small progressive country. There are signs of a growing cultural confidence; the 2022 Welsh FIFA World Cup campaign video was shared with me when I was preparing for my job interview and it made my heart sing. The city of Cardiff itself has changed dramatically – in no small part because of European structural funds – and now regularly features on lists of small liveable cities. Our history as a port city means we have a long experience of ethnic diversity that is now helping us all understand the importance of social inclusion and anti-racism. And finally, perhaps as a reflection of political devolution and that growing cultural confidence, Cardiff is becoming an increasingly Welsh city albeit in a contemporary, multicultural, form that still sets it apart from much of the rest of Wales.

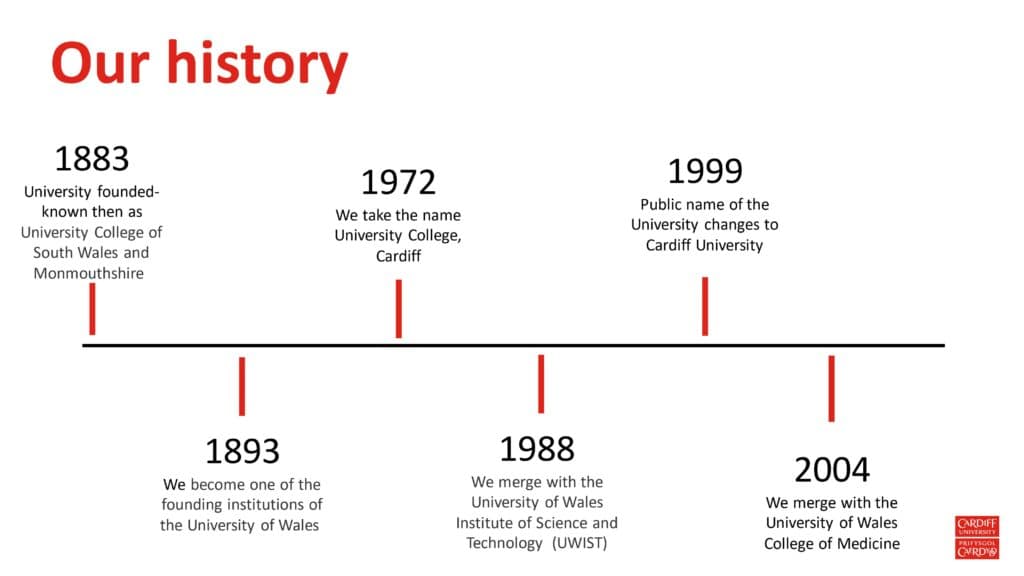

Cardiff University has been an integral part of the story of these changes to Wales and Cardiff. You know better than me that Cardiff University has a complex past and I won’t attempt a history here. Suffice to say we are a much more amorphous creature that the solid white stones of our main building in the civic quarter suggest. The product of mergers and collaborations, we have gone by many names since our founding in 1883. Indeed, what is now “Cardiff University” is a co-mingling of so many institutions, colleges, schools and departments that our archivists have resorted to using a large flow-chart to make sense of it all!

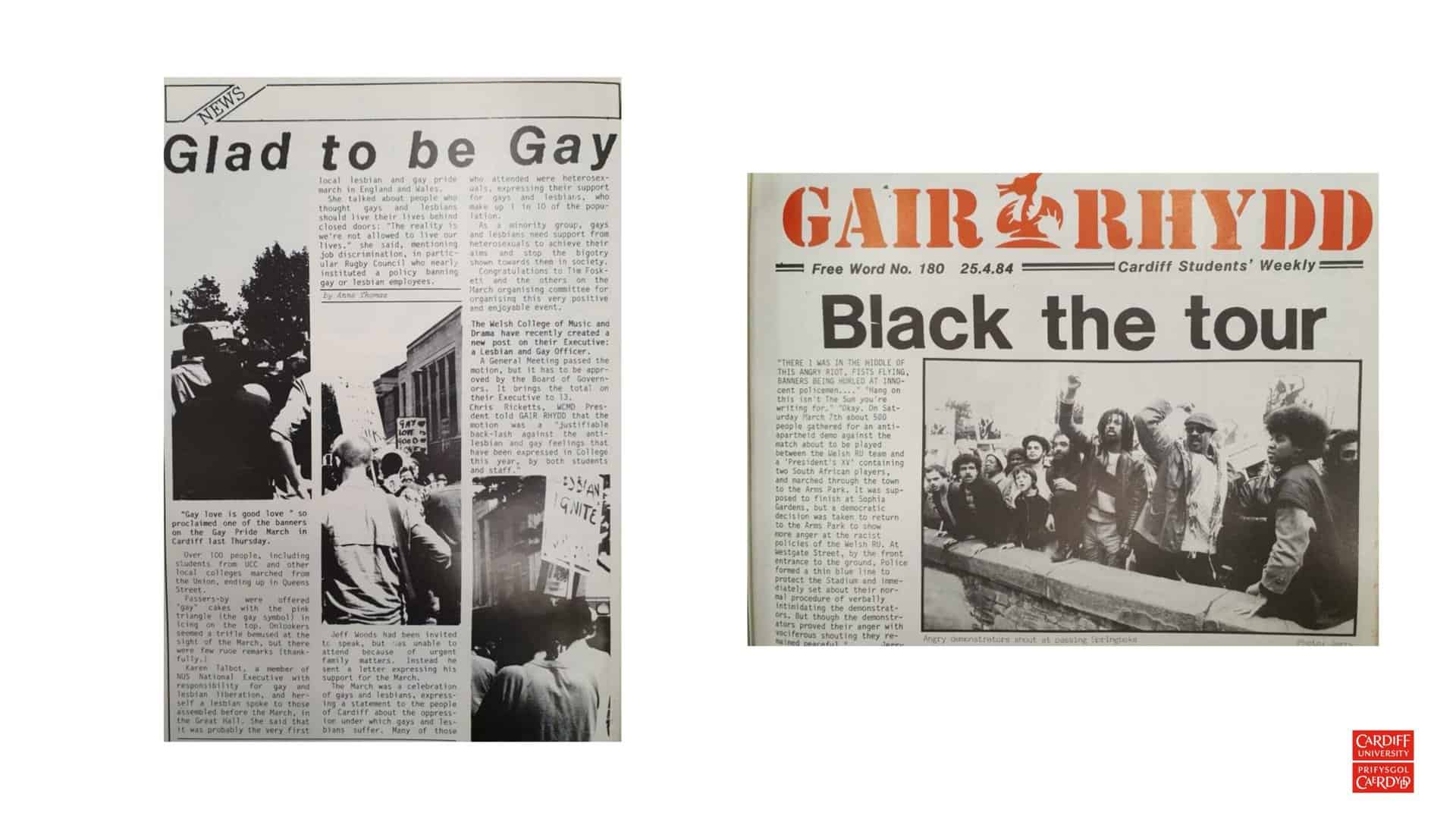

But there are also some enduring themes. Cardiff University has always been a proud civic university, founded in part through a public subscription model that underlined a wider Welsh commitment to education and learning. We were the first Welsh university to admit women, and the earliest chartered university in the UK to employ women as professors (although we didn’t have the first woman Vice Chancellor!). The University has long stood ‘shoulder to shoulder’ with its neighbours in the city of Cardiff, in Wales and beyond. Our archives are full of stories of academic staff and city residents co-operating from the Splott Settlement to the Living Wage campaign. Student volunteerism and activism have a rich history, showing our tradition of enabling free speech and debate, and also of encouraging civic participation and action. Student newspapers show us how passionate and effective our student body has been: protesting for women’s safety; against Apartheid, racism and war; in favour of LGBT+ rights, renters’ rights and much more.

Our commitment to research and education that makes a positive impact can also be traced through our institutional records. We’ve made an enormous contribution to Wales and the world in this regard. Over the years, our staff have contributed to wide-ranging global advances in medical and social care, harm prevention, the reduction of violent crime, renewable energy, counter-disinformation, wellbeing, biodiversity and much more. This is not just research for research’s sake. It is research that makes a difference; it is no coincidence that it was in the area of impact that Cardiff University performed most strongly in the last Research Excellence Framework exercise.

We have educated generations of students who have gone on to have longer, healthier, wealthier lives, and to contribute economically, culturally and socially in their chosen fields including, I suspect, many in this room. Cardiff University staff and students have long been integral to the liveliness of our city through their support of the arts, culture, sports, hospitality, education and health sectors. The increasing diversity of our student population – particularly as the numbers of international students has grown – has further contributed to the cosmopolitan nature of Cardiff. It is well known that today the city attracts up to 70,000 students per year, over half of whom study with us at Cardiff University, and many of whom fall in love with our city and chose to stay, further underpinning Cardiff’s new growth industries, including science and technology, information and communication, and the creative sector.

And here we begin to see the explicit connection back to Doreen Massey. Where it was once extractive industries such as coal mines, today universities have become anchor institutions for the Welsh economy. This is not just for the employment they offer and the contributions we make to the places in which we are based, but because today universities are central to the new ‘growth clusters’ foreshadowed by Massey’s reference to science parks. For example, in their 2024 report Avison Young identified Cardiff as the fastest growing core city in the UK. To quote this report:

Cardiff University alone generated £3.7 billion of economic output in 2020-21, compared to an operating cost of £573 million. This output includes £883 million from research and knowledge sharing, which is boosting the city’s science and technology economy, a sector which is set to grow by 6.6% over the next five years. It is no coincidence that this coincides with a positive outlook for the Cardiff’s labour market. Over the next five years, job growth is forecast at 3.7%, compared to 2.4% for Wales and 3.1% for the UK as a whole, driven primarily by growth in the professional, scientific and technical services sector (6.6%) and the information and communication sector (4.4%).

While too often ownership and control continue to elude us, these ‘growth clusters’ are based on entrepreneurial higher wage, higher skill activities that generate new forms of economic growth. In this regard, I want to recognise the foresight of my predecessor Colin Riordan, and the establishment of the Cardiff University innovation precinct in Maindy Road. This precinct is not just focused on STEM and familiar forms of commercialisation – although we do see those in the compound semi-conductor and catalysis institutes housed in the Translational Research Hub – but also contains the social science SPARK building which also sees us collocated with our community partners. We further contribute to the growth clusters by educating a whole range of specialist workers, creating an intellectually engaging climate in the city, and facilitating new cross-sectoral relationships, and actively creating new businesses.

So the future for Cardiff University, our city and Wales should look bright. We are creating better jobs and career paths, we are growing entrepreneurial professionals, scientists and technologists (albeit still largely through publicly funded and/or state sponsored initiatives), and we better understand the benefits of partnering and co-location in a desirable city. But Cardiff University is also facing challenges and it would be remiss of me not to mention those. Indeed I’m on record as saying that the operating model for Universities is broken, not just here in Wales but more generally. You should all know the issues by now; student fees do not cover the costs of educating our home students, we cannot cover the cost of our research, and it is only international student fees that are keeping us afloat. We will need to be different for the future, and there are hard decisions to make.

That said, I am confident about the future. In my view – because of our history, our people, and our place – Cardiff University has the potential to be one of the world’s great global-civic universities.

Our new strategy

So what will we need to do to realise these ambitions? First, the days of each University trying to be all things to all people are over. In many countries we see greater differentiation, specialisation and collaboration amongst universities and other institutions. For Cardiff, the dominant Welsh research university, building stronger national, UK and international research collaborations, delivering on heightened research ambitions, leveraging the opportunities associated with regional initiatives like the Western Gateway and GW4, and further realising the potential of the new innovation precinct will all be key. But this also means we will have to stop doing some things. We will also need to avoid the temptation to see universities as alternative providers of public services in a context where the NHS and local government are both stretched and stressed.

Slide: Wellbeing of Future Generations

Secondly, it is now widely understood that Universities will need to truly embrace their own context. For Cardiff University, an explicit and enhanced commitment to Cardiff and Wales will be crucial. This is not just about highlighting and embedding Welsh language as an issue of equity and inclusion, we will need to normalise Welshness in all our activities. This will raise important questions about doing more in Cardiff and Wales based on history, place and social justice. We will also need to even more proactively play our role in a future Welsh economy, further leveraging the relationships we have begun to establish through the Cardiff Capital Region, our relationships with the NHS and so on. We need to be not just in Wales, but of Wales – helping co-create a future for this ambitious small country in which more aspects of ownership and control remain with us, and we become much more ‘sticky’ as we contribute to successful growth clusters.

Thirdly, the future University will be more porous. I’m very drawn to Ronald Barnett’s concept of the ‘ecological university’. This is a university that’s deeply networked in society, makes knowledge resources freely available, and engages actively to bring about a better world. It is not an instrumentalist conception of ‘mission led’ research challenges and industry partnerships; our stakeholders will be multi-faceted, including governments, NGOs and communities. Nor is this a matter of linear conceptions where universities disseminate their knowledge to others; this is a world of co-design, co-production and mutual learning. This will have implications for the future of our campus and for our people. For example, as the recent Spinout Review (2024) observes, entrepreneurship requires skills, experience, and infrastructure that Universities have not traditionally possessed. Nor do we have the funding to readily commercialise our activities. If we are to do more in this regard we’ll need to think differently.

Finally, I am very clear our students are at the heart of our future. In this differentiated, place-based, porous ecosystem educational offerings will change. The era of ‘flipped’ classrooms and work integrated learning has well and truly arrived. More generally, enhancing activity based learning and teaching will be crucial, particularly because Cardiff University will continue campus based provision. At the same time, it will be increasingly the case that cities and communities become our campuses. We also need to open up our university to personalised lifelong learning, not in the old fashioned sense of night classes for middle class retirees, but in the modern sense of on demand skills and professional development. In the ecological university students are deeply embedded with many partners in their activities, and our educational role in economic and social renewal is taken seriously. The decline in young people’s participation in education in Wales is particularly concerning in this context, and we must take this seriously.

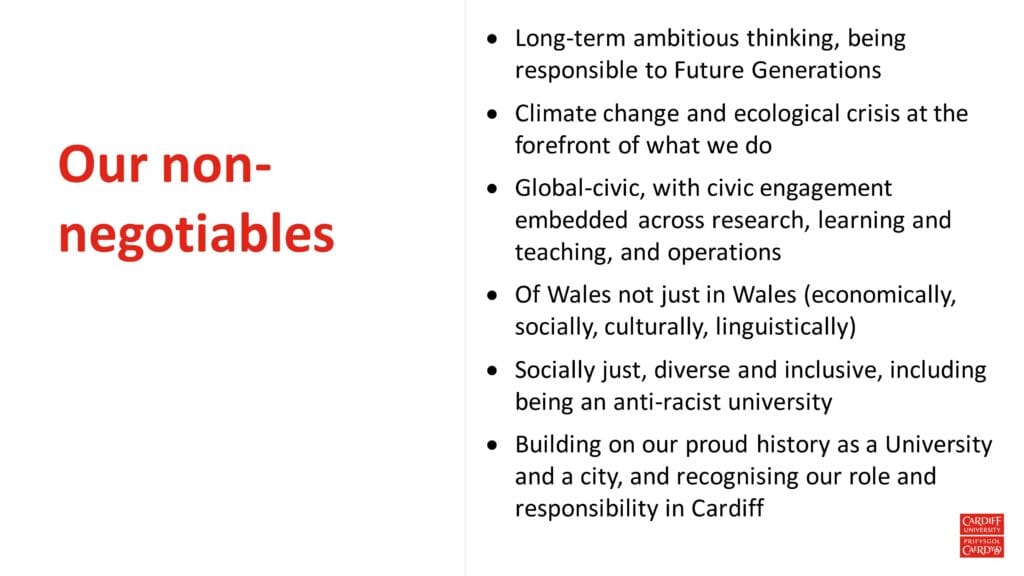

Finally, in my discussions with the staff and students of Cardiff University I have been very clear about the ‘non-negotiables’ for our future strategy and it might be helpful to conclude by sharing these with you before we open up the discussion.

- Long-term ambitious thinking, being responsible to future generations

- Climate change and ecological crisis at the forefront of what we do

- Global-civic, with civic engagement embedded across research, learning and teaching, and operations

- Of Wales not just in Wales (economically, socially, culturally, linguistically)

- Socially just, diverse and inclusive, including being an anti-racist university

- Building on our proud history as a University and a city, and recognising our role and responsibility in Cardiff

In short, it is a time for an ambitious approach, building on the strong foundations Cardiff University offers, to create a University not just of the future but for the future; a future University for a future Wales and for a future world that we can all be proud of.

Diolch!