We should re-define excellence in education if we are serious about closing gender gap in STEM, argues Helen Wollaston, Chief Executive of the WISE campaign

Education system short-changing girls of a bright future in STEM

08 Dec 2016

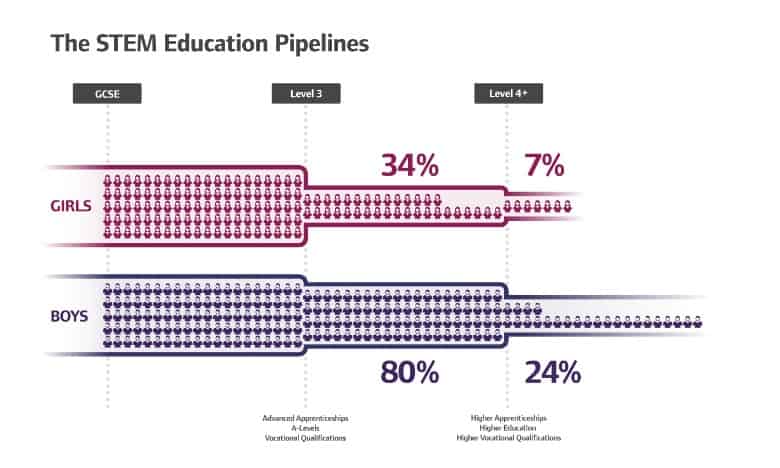

WISE research has identified that just 7% of girls and young women leave the UK education system with a qualification to work in core STEM occupations, compared to 24% of boys and young men1. This gender gap equates to a difference of more than 50,000 students every year. No wonder science, engineering and technology companies struggle to attract female applicants. Demand far outstrips supply.

Aside from the real and ever-more pressing impact on industry – holding back growth in engineering, digital and advanced manufacturing sectors which are so important to the UK’s economy because of skills shortages – there are serious implications for girls and women. Data from the World Economic Forum suggests that for every 4 traditionally male jobs displaced by automation, there will be a loss of 20 traditionally female jobs. Put simply, if we don’t get more girls coming out of education with digital skills, there is a real risk that as a country, we start to move backwards in terms of gender balance in the labour market – with women defaulting to low-paid jobs in the care sector.

If we believe the purpose of education is to help every young person realise their potential, it cannot be right that schools and colleges which are doing nothing to address the gender divide in STEM subjects can be deemed excellent.

WISE is not arguing that every girl should be a scientist, an engineer or a techie but science, engineering and technology define the environment in which we all live. Women are 50% of that world but have very limited sway in shaping it – as an example, in the car industry, 80% of purchases are influenced by women yet women play little or no part in car design and manufacture. It isn’t because women are excluded by the manufacturers, it’s because there are so few STEM-qualified women.

It isn’t the right fit for all girls/young women but it has to be right for more than 7%! Don’t let anyone tell you girls are not good at maths, physics or computing. When you consider the results of those girls who do choose STEM subjects, girls outperform boys at GCSE and GCE levels much more significantly than they do in non-STEM subjects.

We are calling for action on three fronts – education, apprenticeships and industrial strategy. OFSTED should analyse the percentage of girls taking science, maths and computing after GCSE – and only give excellent ratings to schools and colleges achieving 24 per cent. This would match the percentage of boys.

The gender divide in apprenticeships in considerably bigger than in undergraduate courses in higher education institutions. We are therefore asking the Government, with support from many of our corporate members, to relax the proposed rules on the Apprenticeship Levy. If employers subject to the levy could draw down funds to market science, technology and engineering apprenticeships to women and provide additional support such as training for managers, support structures for female students and other positive action measures which have been proven to make a difference, many would leap at the chance. The shockingly low numbers of girls doing the 4 biggest STEM apprenticeships have been largely static for the past 4 years (Industrial applications up 0.1%; construction skills up 0.4%; Engineering up by 0.4% and IT/Telecomms down by 0.3%) Without positive action, a growth in apprenticeship numbers is likely to exacerbate the gender divide. The Levy presents an opportunity to use the funds generated from large employers to make a positive difference.

Both these measures would contribute to the bigger goal – to achieve better gender balance in the UK’s STEM workforce. Because ultimately this would help the UK’s economic position globally in a post Brexit world, our third call relates to the much talked about UK industrial strategy. By setting a bold aspiration that at least a third of jobs in STEM sectors are filled by women, the Government would ensure this issue is where it should be – centre stage, not on the sidelines under the heading of “women’s issues” or “corporate social responsibility”.

We can turn the tide and get more young women choosing science, technology, engineering and maths. We have to take this seriously so that they, and the UK as a whole, will have a brighter future.

1) Core STEM as defined by the UK Commission on Employment and Skills include physical sciences, technology, engineering and maths rather than life sciences where there is a better gender balance at entry level.

Related articles

The Physiological Society’s policy team on the health challenges facing older workers and the urgent need to develop a strategy to ensure older people are happy and healthy at work.

Jo Reynolds, Director of Science and Communities at the Royal Society of Chemistry, on the RSC’s new summary report looking to unlock the potential of deep tech SMEs.

Lisa Morrison Coulthard, Research Director at the National Foundation for Education Research, on the Nuffield Foundation funded five year research programme providing insights into the essential employment skills needed for the future workforce

Sir Adrian Smith, Institute Director and Chief Executive of The Alan Turing Institute, and Graeme Reid, Professor of Science and Research Policy at UCL, set out the findings from their new independent report on international partnership opportunities for UK research and innovation