Louise Archer, director of the ‘Enterprising Science’ education project on the advantages of a science capital teaching approach.

Increasing student aspiration and engagement: A ‘science capital’ teaching approach

13 Oct 2017

On 13th October 2017, we launched a new teaching approach. Four years in development and trialling, the approach was co-designed by teachers in London, Newcastle, York and Leeds and researchers from University College London and King’s College London as part of the ‘Enterprising Science’ project. Our hope is that the approach will offer new hope to the long-standing challenge of how to better engage more young people, from more diverse backgrounds, with science. And analysis of the findings seems promising!

What is the science capital teaching approach?

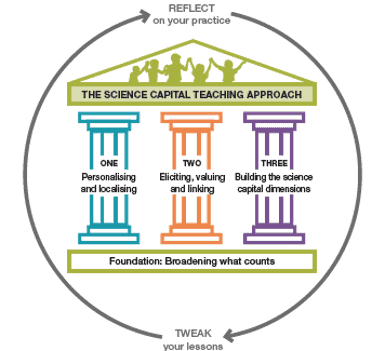

The approach is designed to work with any science curriculum. It’s not a new set of materials, rather it is a reflective framework, or ‘mind set’, through which teachers tweak and re-orientate their lessons, to better connect science with their students’ lives and experiences.

Based on the idea of broadening what counts as teaching and learning science, it comprises three main pillars (see Fig 1):

(i) Personalising and localising – this goes beyond contextualising science, to help students find personal meaning and connection with science.

(ii) Eliciting and valuing students’ experiences, identities and interests in class, and linking these to the science content.

(iii) Building the dimensions of science capital – for instance, a teacher might regularly highlight how what the class are learning can be useful for any career, not just science jobs.

The idea for the approach developed from our previous research, notably the concept of science capital – that is, the science-related resources that someone possesses, such as their science-related attitudes and dispositions, knowledge, interests, behaviours and social contacts. Prior research found that the more science capital a student has, the more likely they are to see themselves as a science person and aspire to continue with post-16 science. Through Enterprising Science, we wanted to explore how and if we might be able to increase student science capital.

What did we find?

Over four years we worked with 43 secondary science teachers. We chose to work in depth with schools with high proportions of students from socially disadvantaged communities. The latest 2016/17 trial included pre/post surveys with 244 intervention students and surveys with 1,871 comparison students (who did not experience the approach) We also conducted classroom observations, discussion groups and interviews with students and staff.

We found that:

- Intervention school students began the trial with significantly lower levels of science capital than both the national average and comparison students. But by the end of the year, intervention students had closed the gap with comparison students, recording a statistically significant increase in their science capital.

- Students who were taught using the approach expressed much more positive views of science and its relevance to their lives in their post-intervention surveys

- There was an increase in the percentage of students saying they would like to study one or more science subjects at A level, from 16% (pre-intervention) to 21.4% (post-intervention)

- Students reported increased regular engagement with science outside school – and decreased percentages of students who ‘never’ do science activities outside of school – e.g. going online to look up things about science; talking with others about science.

Students and teachers liked and benefitted from the approach and felt it helped students to find meaning in, and connect with, science and improved students’ understanding of science concepts and content, as they found science more relatable. As one boy put it, “Yeah, I feel like we get a better understanding because we can relate to what [teacher]’s teaching us”. Some classes also recorded marked gains in attainment.

Teachers agreed that using the approach increased student engagement with science, led to better understanding and improved behaviour. As one teacher explained: “What I’ve noticed is when I use the approach, I can see it in their eyes…like meerkats, they pop up and you can see the engagement”. Another reflected: “More students get more work done and there’s less disruption. There’s more interest”.

We hope that the findings and approach will be of interest to science teachers and educators – and we welcome further dialogue.

The research was conducted as part of the Enterprising Science project, a five year collaborative partnership between University College London, King’s College London, the Science Museum Group and funded by BP. Contact details: ioe.sciencecapital@ucl.ac.uk. Twitter: @_ScienceCapital.

Related articles

The Physiological Society’s policy team on the health challenges facing older workers and the urgent need to develop a strategy to ensure older people are happy and healthy at work.

Jo Reynolds, Director of Science and Communities at the Royal Society of Chemistry, on the RSC’s new summary report looking to unlock the potential of deep tech SMEs.

Lisa Morrison Coulthard, Research Director at the National Foundation for Education Research, on the Nuffield Foundation funded five year research programme providing insights into the essential employment skills needed for the future workforce

Sir Adrian Smith, Institute Director and Chief Executive of The Alan Turing Institute, and Graeme Reid, Professor of Science and Research Policy at UCL, set out the findings from their new independent report on international partnership opportunities for UK research and innovation