Jack Worth, Senior Economist at the National Foundation for Educational Research, on the maths and science teacher supply challenge facing schools.

Is England running out of maths and science teachers?

10 Jul 2017

Concern about the supply of secondary school teachers in England has been growing over recent years due to rising pupil numbers, increased rates of teachers leaving the profession and shortfalls in the number of teacher trainees. Each of these factors have been particularly acute for maths and science teachers.

Demand for maths and science teachers has increased over the last five years and is expected to increase further. The number of secondary school pupils in state-funded schools is projected to increase by 20 per cent between now and 2025, increasing the number of teachers that the system needs just to stand still.

New school accountability measures have also been introduced, which have maintained the importance of maths and science in the school curriculum. Maths and science (along with English, history, geography and modern languages) are both subjects that make up the English Baccalaureate. The new headline accountability measure for secondary schools, Progress 8, gives schools greater incentives to ensure pupils achieve good GCSE grades in EBacc subjects and lesser incentives for pupils’ achievements in non-EBacc subjects (such as arts and technology subjects).

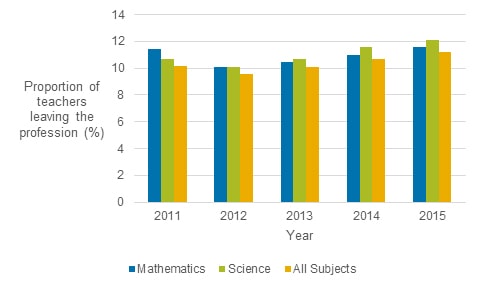

Meanwhile, it has been getting more difficult for schools to retain and recruit maths and science teachers. The proportion of teachers leaving the profession each year has risen since 2012 for all subjects. Data published by the Department for Education in May 2017 shows that the leaving rate for maths and science teachers has been consistently higher than average (see chart). Our recent analysis of teacher retention rates shows that leaving rates are particularly high among maths and science teachers in the first five years of their career, whereas retention rates for mid-career teachers are more similar to average.

The rate of maths and science teachers leaving the profession each year is higher than for other subjects

Low teacher retention rates mean that more new entrants are needed for the system to keep up with demand. Government data on the number of new trainees shows that the number of maths and science trainees is below the level required to keep up with demand and has been for several years in a row.

All these factors combine to paint a challenging picture for the supply of maths and science teachers, now and in the years ahead.

What can policy do to maintain teacher supply?

One of the Government’s main policies for ensuring an adequate supply of maths and science teachers is to offer generous bursaries for training to be a teacher. Maths and physics graduates will receive at least £25,000 for training to be a teacher in 2017. However, these payments are received for completing training and are not conditional on entering, let alone staying in, the teaching profession.

Financial inducements to train to teach in shortage subjects may be more effective if they explicitly incentivise retention in the teaching profession during the first few years after training. The 2017 Conservative party manifesto contained a pledge to “offer forgiveness on student loan repayments while [teachers] are teaching”, which seemed to suggest some action along these lines. However, given the uncertainty about what aspects of the manifesto will be taken forward, it is not clear whether the Government now intends to introduce such a policy.

Our research has found that there is much that schools can do to improve retention. The research found that teachers with a high level of engagement – a measure that includes job satisfaction, the feeling of reward and recognition, and being well supported by management – strongly influences teacher retention. It suggests that headteachers can improve the chances of keeping their staff by improving engagement.

However, the research also found that science teachers are still more likely to be considering leaving the profession, despite their relatively high level of engagement. This hints that there are unique factors about science teachers that make them more difficult to retain. Relatively low teacher pay may be in important factor for whether science teachers stay in or leave the profession. STEM qualifications command a relatively high return in the wider labour market, meaning there may be better-paid opportunities beyond teaching for many science graduates.

Teacher pay growth has been below the growth of average wages outside teaching and inflation for several years because of the public sector pay cap. Research by the IFS has shown that the retention rate of early-career maths and science teachers is particularly responsive to the wage rates on offer outside of teaching in the local area. This suggests that restraints on teachers’ pay has contributed to some extent to the particularly challenging situation of maths and science teacher supply, especially in high-wage areas such as London and the South East.

There are no easy answers to solving the challenge of maths and science teacher supply, but solving it is essential for maintaining the pipeline of STEM skills for decades to come.

Related articles

The Physiological Society’s policy team on the health challenges facing older workers and the urgent need to develop a strategy to ensure older people are happy and healthy at work.

Jo Reynolds, Director of Science and Communities at the Royal Society of Chemistry, on the RSC’s new summary report looking to unlock the potential of deep tech SMEs.

Lisa Morrison Coulthard, Research Director at the National Foundation for Education Research, on the Nuffield Foundation funded five year research programme providing insights into the essential employment skills needed for the future workforce

Sir Adrian Smith, Institute Director and Chief Executive of The Alan Turing Institute, and Graeme Reid, Professor of Science and Research Policy at UCL, set out the findings from their new independent report on international partnership opportunities for UK research and innovation