Roger Highfield, director of external affairs at the Science Museum Group, talks about valuing science – not just by Government but as a pillar of culture

Time to put science back at the heart of national culture

28 Nov 2016

Once upon a time, civil servants would roll their eyes and grumble that there was too much science, some commentators argued that research should only be funded by industry, and officials from the Treasury told a Select Committee that there was no relationship between research and the health of the economy.

Those were the darkest days of British science some three decades ago when the President of the Royal Society, Prof Sir George Porter, told me that the morale of the scientific community had fallen to its lowest point in the 20th century and that ‘we shall soon live in a country which is backward not only in its technology and standard of living but in its cultural vitality.’

Today, of course, Save British Science has evolved into the Campaign for Science and Engineering: science no longer needs to be saved – the Government has given assurances about safeguarding research and innovation – and the importance of scientific research for the economy has been underlined again and again, for instance by the Royal Society and CaSE.

But I am unconvinced science has regained its rightful place in national culture.

As one of the Directors of the Science Museum Group, I have a unique perspective. Where I now work in South Kensington was once devoted to both arts and sciences, thanks to Prince Albert (hence ‘Albertopolis’). On the V&A’s original 1868 vintage bronze doors, three figures from the history of science are balanced by three from the arts.

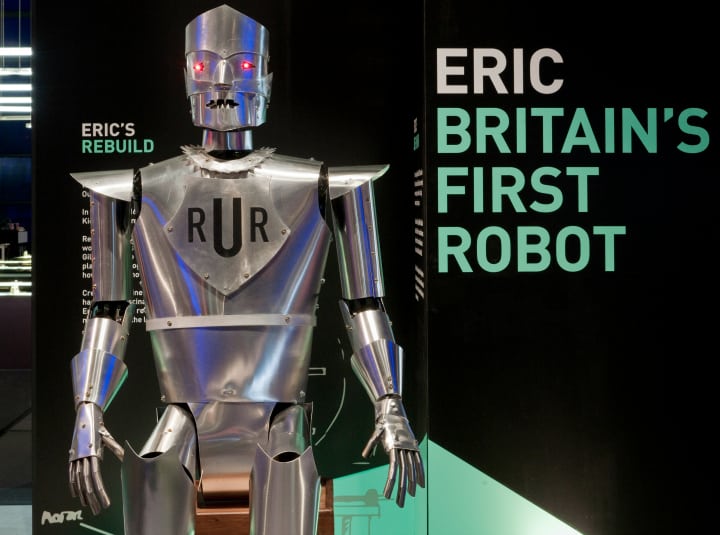

Today, in addition to the Science Museum, we also have museums in Manchester, York, Bradford and Shildon, which are also funded in part by the Department of Culture, Media and Sport and together provide a nexus for Government, industry, researchers, historians, seven million historic objects, 600,000 schoolchildren and around five million members of the public each year. Our exhibition about the LHC (Collider) has been seen by more than half a million people worldwide; our critically acclaimed exhibition on the birth of the space age, Cosmonauts, has opened in Moscow (as the Russians say, it’s like travelling to Tula with one’s own samovar); and we’re working hard to turn Robots into another blockbuster exhibition when it opens next February.

Science, through its application in innovation, is now changing culture more rapidly than ever and, if I gaze into my crystal ball at how museums will evolve during the next three decades, I envisage a shift in collections from material to virtual culture, not just digitized objects but software, algorithms, AI, games, social media and so on.

But in one sense we have gone backwards. A crude analysis of the recent White Paper on culture mentions the word ‘culture’ 426 times, ‘art’ 77 times, ‘music’ 28 times and ‘science’ only 10 times. Look at the DCMS guidelines for the City of Culture, and you find that science ‘may be included’ but should not be a major element of a city’s bid. This tells you everything you need to know about the precarious place of science in today’s culture.

To shore up its standing, only part of the answer will come from enlightening the cultural establishment (or should that be luvviocracy?) We need to reform the scientific establishment too where, despite efforts to boost diversity, there has long been under-representation of the working-class. Even though our museums are free to visit, great swathes of the population are not interested. That is why we are working on a new approach to science engagement (Science Capital) with King’s College and BP, and doubling the number of schoolchildren – our most demographically representative visitors – going through our new Wonderlab: the Statoil Gallery to 200,000 each year.

This is critical because the impact of the scientific method on everyday life is ubiquitous, indisputable and increasing. Science’s culture of scepticism, testing and provisional consensus-forming is without doubt the most significant achievement of our species. We need to do more to restore science to its place at the heart of national culture.

Roger Highfield is Director of External Affairs, Science Museum Group, and sits on the Royal Society’s Science Policy Advisory Group.

Related articles

Dr Christoph Hartmann is Medical Director, MSD in the UK, a CaSE member. In this piece he sets out he would like to see form the new government to support UK life sciences and innovation.

Will Lord is Head of Government Relations at the Aerospace Technology Institute (ATI). In this piece, he sets out the strengths and successes of the UK aerospace sector, as well as the advantages of business-government collaboration.

Joseph Ewing is Head of Policy and Public Affairs at LifeArc, the sponsors of CaSE’s work looking at the needs of business R&D in the UK. In this piece he sets out why the project is needed, and why we should all care about business investment in R&D.

Tamsin Mann, Director of Policy & Communications at PraxisAuril, on the importance of understanding and unlocking the full potential of knowledge exchange.