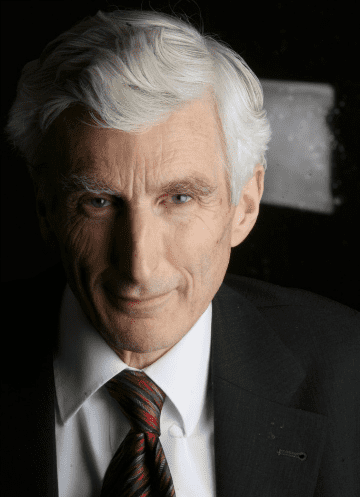

Lord Martin Rees, Astronomer Royal and former president of the Royal Society, talks about the worries of a post-Brexit Britain and hopes that the value of collaboration isn’t ignored.

UK Science is better connected

25 Nov 2016

This year’s Nobel Physics Prize was shared between three Brits for work mainly done in the UK around 1980. But all three defected to the US during the Thatcher years, when university budgets were heavily squeezed and job-opportunities were scarce. That was the era when CaSE was founded, under its original name ‘Save British Science’.

Fortunately, prospects for UK science have somewhat brightened in the subsequent decades – enough, anyway, to justify CaSE’s decision to drop its original name. We continued to spend a smaller percentage of GDP on research than our competitors, but it was some consolation that science was protected in cash terms by the coalition government.

League tables can be misleading (I think they do more harm than good) but given that they exist we should be gratified that the UK comes second only to the US (with more than 5 times our population) in most science-linked ones. And we are second only to the US in attracting foreign students to our universities – with ensuing benefits not only to the economy, but to our long-term ‘soft power’ worldwide.

Moreover, over the 30 years of CaSE’s existence we’ve had genuine ‘brain gains’. Among these were the current President of the Royal Society (who came from the US); and the discoverers of the wonder-material graphene, (who came to this country from Russia, via a stay in Holland).

So what is the prognosis for the next 30 years? I think we’ll have a bumpy ride. In the immediate future, Brexit, and its impact on the perception of our country, is of course a threat.

Much of the improvement in UK science is owed to strengthening links with Europe Some of Europe’s greatest technical successes – in particle physics and in aerospace, for instance – have required multinational collaboration. CERN and the European Space Agency are underpinned by international treaties: they aren’t directly linked to the EU. However, our collaborations -and our attractions as a partner and a destination for mobile talent – would be jeopardized by Brexit. Academia and high-tech industry in this country benefit hugely from talent attracted from across the EU. The younger generation, especially, see themselves as ‘Europeans’ with a shared culture, and recognise that our continent can be a progressive political force in a turbulent and multipolar world.

And the key challenges –issues like bio and cyber-security, and avoiding environmental degradation, must be handled at a continental (if not global) level. And so must the crucial transition to economical low-carbon energy generation: this requires enhanced R and D, and in the longer run a new pan-European grid.

These challenges offer huge opportunities where Europe can take a lead – but have downsides too. Scientists should try to foster benign spin-offs – commercial or otherwise – but should campaign against dubious or threatening applications of their work.

A special obligation lies on those in academia, and on self-employed entrepreneurs – these groups have more freedom to engage in public debate than employees of government or industry. Politicians think parochially, and look towards the next election. Financiers, too often, look to the next quarterly statement. Scientists, as a community, are better at thinking long-term and globally.

“Space-ship Earth” is hurtling through the void. Its passengers are anxious and fractious. Their life-support system is vulnerable to disruption and break-downs. But there is too little planning, too little horizon-scanning. Without a broader perspective – without realizing that we’re all on this crowded world together – governments won’t properly prioritise projects that are long-term in a political perspectives, even if a mere instant in the history of our planet. Just as the UK is a leader in science so it can spearhead these advances.- the whole country suffers if our hard-won scientific excellence spirals into decline. The maxim ‘if we don’t get smarter, we’ll get poorer’ will apply even more powerfully if we have to contend with the fallout from Brexit. Let’s hope that CaSE doesn’t have to revert to its original name.

Related articles

Dr Christoph Hartmann is Medical Director, MSD in the UK, a CaSE member. In this piece he sets out he would like to see form the new government to support UK life sciences and innovation.

Will Lord is Head of Government Relations at the Aerospace Technology Institute (ATI). In this piece, he sets out the strengths and successes of the UK aerospace sector, as well as the advantages of business-government collaboration.

Joseph Ewing is Head of Policy and Public Affairs at LifeArc, the sponsors of CaSE’s work looking at the needs of business R&D in the UK. In this piece he sets out why the project is needed, and why we should all care about business investment in R&D.

Tamsin Mann, Director of Policy & Communications at PraxisAuril, on the importance of understanding and unlocking the full potential of knowledge exchange.