Dr Catherine Pointer, from the Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre in Southampton, talks about her appearance at Voice of the Future and her inspiration behind her work

Inspiration for science – why personal experiences matter

22 Apr 2021

On the 10th March 2021 I was given the opportunity to ask MP Shadow Minister for Science, Research and Digital, Chi Onwurah, a question of my choosing on behalf of CaSE at the Voice of the Future virtual event. My question related to how the coronavirus pandemic has caused unprecedented disruption to an entire generation of school children and potential future scientists. Not only have children and young people missed their science lessons, they have also missed out on school trips and engagement projects, which would usually inspire young people to pursue higher education and a career in science. The pandemic has also resulted in a drastic loss of funding for school and public engagement programmes in science. With this in mind, I asked how should the UK seek to increase the opportunities for children to experience science so that the next generation of scientists isn’t lost?

My question was well received and sparked a brief conversation about the challenges faced by young people wanting a career in science despite the disruption of the last year. For me, the challenges faced by today’s students are all too familiar with my own experiences in my education as a teenager, and so for me, my question was an obvious one to ask.

If you ask someone why they became a scientist, the answer is rarely just because they liked their lessons in school. It’s usually because they met a scientist or went on a school trip, or were personally affected by something, and then realised that a career in science could be for them. As a child I always thought the idea of being a scientist was exciting but found my everyday lessons quite uninspiring and assumed it wasn’t a possibility for people like me, who went to average (or below average) schools. It wasn’t until my own experiences with cancer I discovered not only that scientific research was doing amazing things, but that even I could do it.

When I was 14, I suddenly because ill and after weeks of relentless testing I was eventually diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. For the next year my education went completely out the window. But on the hospital ward, my consultant noticed my reaction was different to other teenagers my age. Whilst others asked, “why me?”, I was asking “how me?”. How does a healthy 14-year-old with no family history of cancer, who hasn’t smoked or done anything to damage themselves, get leukaemia? Where did it come from? What is cancer? I would sit with my doctors and they would answer my questions as best they could, but there would always come a point in the conversation where the answer would be “no one knows, that’s what research is trying to find out”. It was in these conversations with real doctors and scientists I realised that research was truly fascinating and even I could become a scientist myself. I didn’t need to be a super genius or go to the best schools. But as I realised I wanted to be a scientist, my education was falling by the wayside, and I completely missed year 10.

After returning to school and managing to scrape together far fewer GCSEs than I should have, the leukaemia suddenly returned when I was doing my A levels. I had to take a full academic year out while I had a bone marrow transplant. When I returned, I did my best to use my experience to my advantage and even cited my own illness as work experience in my personal statement for university applications. But the sheer stress of trying to catch up and attain an education in a subject which is already viewed as difficult, was at times overwhelming. It was very tempting on many occasions to just give up. Sadly, many people were of the view that I simply shouldn’t bother returning to my education and should ‘just go get a job’. This was an attitude held by many friends and family of other teenage cancer patients as well. Of all the friends I made during my time in hospital, almost none pursued higher education. I am the only patient I know who now works in a STEM subject. School, exams and the pressures of education are difficult enough at the best of times. When life then falls apart, it’s seems logical to many people that you should cut out anything else which is causing your stress. But for me at least, cancer presented itself as a problem which will continue to ruin lives until we do something about it. I wanted to do something about it, and that required me to have a higher education. Whilst I often cursed the stress, it all became worth it the day I finished my PhD, and I will never apologise for refusing to give up.

I cannot help but draw parallels between my own experiences and those of our nation’s students in the last year. The pandemic has stopped their education. Whilst huge efforts were made to try and continue educating children and young people, for the last year, no student has been on a science school trip, been to a museum or done work experience. The stress of trying to keep up with standard lessons and the total lack of external engagement with real life science may result in huge numbers of students simply giving up on their hopes of becoming scientists. Additionally, the vast loss of funding in science has suffered has also resulted in almost complete loss of public engagement activities, virtually or otherwise. But Coronavirus, whilst having a very negative impact on education, has also peaked the nations interest in science and scientists. The pandemic, science and scientists have been mentioned by every news outlet every day for the last year. In the same way I was full of questions about my cancer, the nation’s children have undoubtedly had endless questions about the virus that has turned their lives upside-down. We currently stand in a brief window of opportunity to strike while the iron is hot and capture the imaginations of children and young people, to pave the way for them to become the next generation of scientists. It’s a challenging task and one which would be all too easy to not bother with. But if this year has proven anything, it’s that we simply couldn’t live with the alternative.

See more from this year’s Voice of the Future event.

Related articles

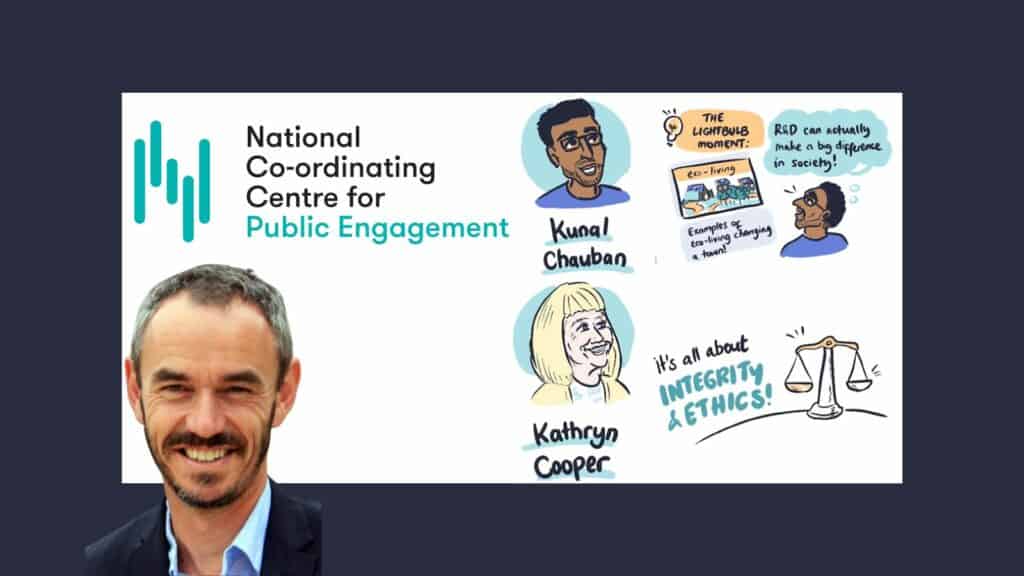

The People’s Vision for R&D was a public dialogue project CaSE commissioned to explore society’s stake in R&D. The project was run by the National Centre for Social Research and the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement. Here, NCCPE Co-director, Paul Manners, blogs about his experience of the project, and shares some personal lessons learned.

Tamsin Mann, Director of Policy & Communications at PraxisAuril, on the importance of understanding and unlocking the full potential of knowledge exchange.

Jillian Sequeira on this weekend’s March for Science and the importance of funding scientific research and creating evidence based policy

Roger Highfield, director of external affairs at the Science Museum Group, talks about valuing science – not just by Government but as a pillar of culture